So do I: otherwise you might not be able to live with yourself after what is to come… P.S. Yes, I accidentally built two stoves.

This War of Mine starts slowly. Closer to The Sims than the Siege of Sarajevo, one directs several (the exact number is procedurally generated) healthy, happy displaced people squatting in a disused house decrepit and strewn with rubble. The squatters clear away the rubble and ransack the disused house. With the ransacked supplies the squatters begin to refurnish the house: An ersatz stove? A mattress supported by bricks? Then night falls. The squatters may sleep (in a bed if they have built themselves such a luxury—but only one to a bed at a time), guard the house, or scavenge nearby inhabited or abandoned buildings.

These nocturnal excursions start simply: there is so much valuable salvage that it is easy to treat much of it as flotsam. (However, one must prioritise scavenging and the use of scavenged salvage intelligently, or suffer the consequences immediately or perhaps weeks in the future.) And everyone has a full stomach, books to read, fags to suck and Joe to swallow. Then someone knocks on the door with a typically confronting videogame moral conundrum such as: Our mother is sick, won’t you please give us some medicine so she doesn’t die a horrible death? P.S. Our father is dead. Sure, why not? After all, supplies are plentiful, and everyone is full and happy. What could possibly go wrong? Nothing. And nothing does.

It is an absurdly misleading opening. (At least sometimes it is: the minute details of how This War of Mine unfolds are procedurally generated so that each playthrough is different—successfully infusing the overt structure of This War of Mine, seasonal events activate at predetermined times to a familiar rhythm, with a sufficient variety for multiple playthroughs. Consequently, not all playthroughs are created equal.)

But, then, many of the buildings so rich with easily accessible salvage become inaccessible due to fighting. Winter falls and, suddenly, not only must everyone remain well fed, well rested, but also warm—using up resources otherwise spent on furnishing the house or cooking or purifying water (at least catching rats for food is unaffected!). Then bandits begin to attack with a clockwork regularity before there is time to celebrate the spring. One’s own temptation to steal is tempered by the crushing guilt endured by the squatters as a result of their kleptomania. Trading is often useless (unless one is desperate and must sacrifice one precious resource for another) without the luxury of a skilled trader and a steady supply of moonshine to barter with.

And, by now, those several squatters might be plus one—another typically affecting videogame moral mystery: give shelter to someone who needs it? But, atypically, much thought must be given to this decision. Each squatter has his or her own special ability. Although this special ability might be invaluable, and an extra body on guard duty is always welcome, another helper also means another mouth to feed; another fragile human being to keep from the brink of suicide. Indeed, every moral decision is given genuine weight not due to the melodramatic, overwrought and, frankly, idiotic at times writing (one squatter was broken by the death of another, but updated his bio with the enthusiastic entry: Better him than me!), but due to their intrinsic, sometimes ambiguous, link with the gameplay mechanics.

The sacrifice of manpower or resources to help another will likely lead to a reward, but what if nobody survives (physically or mentally) to make use of that reward? Yet, even if desperate, turning away a beggar in and of itself will still depress the empathetic squatters. But, even if rich, helping a beggar in and of itself will still depress the despotic squatters. And a depressed squatter is only one step away from a dead squatter.

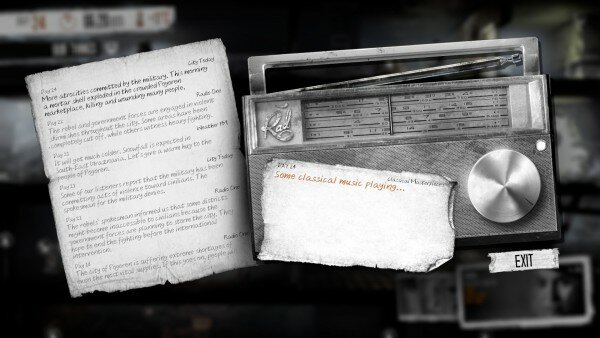

The radio is important: not only does it forewarn one of coming atrocities, but also plays soothing (read: unbearable) muzak.

This intrinsic link between mechanics and theme also imbues the squatters with an anecdotal (the stories I could tell!) and deliberate (the squatters’ ethics change based on their experiences) pathos in spite of their bios—backstory and diary—and unspoken dialogue: it is not hard to empathise with a vitally important squatter when they are suffering because, if they die or give up, then it might mean the end of that playthrough. Admittedly, when my last surviving squatter on my first playthrough committed suicide on the night before the day the war was to end (speculation based on radio chatter), I was more annoyed than saddened. Broken on the penultimate day, she refused to do anything to cheer herself up; even though I had been careful to procure enough coffee (her only vice) that she might enjoy a cup. But, instead, she merely knelt lamenting the night’s raid. (Which had cost her nothing: I’d whisked her, and all her scant remaining supplies, away to safety overnight.)

But I was to blame. The day before I had run out of medicine. I could not leave her at home to be badly wounded in the inevitable raid which would rob her of everything she had and, so, I forced her to sleep the whole day—thus preventing her from making herself a cup of coffee—to be rested for the night. If I had left her to her own devices, perhaps she might not have ultimately killed herself only hours from rescue. Or her illness might have grown worse (sleeping does wonders for the ill and wounded), and killed her on the same night she committed suicide.

Due to the complexity of simultaneously running a household, scavenging and comforting, each seemingly irrelevant choice can have unforgiving and unpredictable consequences. But the underlying mechanics which govern these consequences are always fair—except when they’re not: items, squatter ailments, traders’ inventories, are all procedurally generated (within the parameters set by the game mechanics and one’s actions and the conditions of the squatters) which can, sometimes, result in vastly different outcomes within identical parameters. At the beginning of one day (the end of one session), things were reasonably bad: three out of four squatters were severely ill. But, when I started the same day in the next session, the morning summary informed me that three out of four squatters were terminally ill! Of course, conversely, this system can be advantageous to the player—if things are looking very bad: keep restarting the day until things improve.

But this inconsistency affects more than those who wish to game the system, detracting from the tangible finality and tension which make the gameplay otherwise so engrossing. Those who are not gaming the system but simply must stop might be rewarded or punished simply for stopping. This is especially frustrating when one has played through a day, made a great deal with the door to door tradesman, only to have to stop for one reason or another during that night’s scavenging—This War of Mine saves only at the start of each day—then, on the second attempt when one has time to play, the door to door tradesman’s stock is diminished to the point of uselessness.

The inability to fast forward time is even more frustrating. Each day lasts a good ten minutes, and although one can skip ahead to the night, skipping ahead means that one cannot run a nocturnal household; which is necessary during hard times—the entire war except for the procedurally generated moments of relative leisure. Thus, for ten minutes at a time, one will regularly have nothing to do but to watch the squatters sleep.

Whilst scavenging, the scavenging squatter might encounter hostile people: ordering the squatter to leave, simply attacking the squatter or acting as another complex binary interrogation of moral integrity: intervene as a drunken soldier coerces a helpless woman into sexual submission? In response one might run or fight. But combat is an awkward, point and click encounter using the variables of weapon power and combatant positions inconsistently.

The stealth, at least, is better; if only in its simplicity. One must be careful to peer through keyholes before pushing doors open if something is making a sound on the other side of the door; must always be aware of line of sight near staircases, ladders and open doors; must be careful of how much noise the squatter makes in their scavenging. Although the threat of danger is usually overstated (it’s very easy to run away), hostile discovery means that the scavenging trip is all but over and, combined with the desperation of the resource management, the scavenging is often intense in spite of the lacklustre combat. In fact, it’s often best to simply avoid combat: killing people wreaks havoc on the conscience after all—unless killing a pantomime villain in a moral charade.

When things are bad, even running the household is nerve-wracking. If the squatters are broken, they must be fed and have their wounds and illnesses treated by other squatters; offering time consuming moral support in between chores: the cooking must still be done, everyone must still have their share of sleep, and the furnishings must still be maintained (heaters aren’t going to feed themselves wood, the wood isn’t going to chop itself) or improved. And when night falls, even if everyone is well rested, would it be better to risk an injured or wounded squatter’s ailments in the search for salvage or the protection of the house—or rely on what little supplies remain, and have them sleep so that their ailments might improve faster, at the risk of theft and violence? And maybe some squatters aren’t quite so useful, or likeable, as others…

That is a videogame moral riddle worth unwrapping.